How American hegemony hijacks semiotics

8 min read

Jun 29, 2025

Tribalism is an old, seemingly inevitable fact of American life. Everyone has opinions, none appear compatible, and the American political system remains a wreck; one which the rest of the world gawks at like a crowd watching a public execution. But this ideological division does not occur as per the centrist viewpoint: that Americans simply want radically different things, leading to an ideological conflict. To many, making the two sides collaborate would be like fitting a square peg into a round hole — it’s simply impossible.

The object of this article is to focus most of all on how the centrist narrative isn’t sufficient to explain why we are divided as a country. This leads to my thesis: Division in modern America is a problem of signification, not of belief.

Before I go any farther, I think it’s necessary that I diagnose the main source for this division. I believe the answers are found in Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek, who applied the Lacanian point de capiton (a theory from French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan) to ideology in his book The Sublime Object of Ideology,

… the multitude of ‘floating signifiers’, of proto-ideological elements, is structured into a unified field through the intervention of a certain ‘nodal point’ (the Lacanian point de capiton) which ‘quilts’ them, stops their sliding and fixes their meaning.

Ideological space is made of non-bound, non-tied elements, ‘floating signifiers’, whose very identity is ‘open’, overdetermined by their articulation in a chain with other elements — that is, their ‘literal’ signification depends on their metaphorical surplus-signification.¹

A floating signifier is an unsignified element in a signifying chain. This is a massive part of Zizekian ideology critique, being the means by which the subject is able to embrace contradictions.

Let’s take communism: communist states in the past have been brutal and tyrannical. Yet, communists to this day believe that such systems are integral for human flourishing and freedom. How is restricting freedom necessary for freedom? Because the floating signifier (freedom) is ‘quilted’ into the authoritarian (communist) ideology. Thus, ‘freedom’ is signified as ‘communism’, and vice versa. Other ideologies are not signified as free, but communism is, so the communist state is ‘free’ because all that isn’t communism is innately ‘unfree’. Therefore, communism is synonymous with freedom, both by process of elimination and direct association.

During this process, the ideology retroactively changes any past experiences, memories, and beliefs, and alters them to fit within the ideological framework. The communist sees their comfortable upbringing as a product of bourgeois privilege in the face of widespread struggle; the fascist sees their diverse schooling as the death of authentic culture and heritage, and so on.

By applying the aforementioned theory, I believe division is thus not just a problem of conflicting signifiers, but a problem of competing signification.

Donald Trump ran on a working class and populist basis. This is nothing new. What he did remarkably well was take working class concerns, like the price of eggs and milk, or housing costs and job security, and signify them into a right-wing quilt (rising housing costs are not an inevitable product of an unregulated free-market, but a product of immigrants, minorities, environmental regulation, and so on).

Such economic logic operates like this: The working class is only struggling because the wealthy are, too. They’re overregulated and tax dollars for social programs are in fact corrupt, as those are used and abused to exploit the victimized wealthy, who demand tax cuts and deregulation. The demanded upward transfer wealth manifests in the greater economy, which manifests in the working class’ collective wallet. In other words, the wealthy are suffering because of leftist regulation, and the economy is bad, therefore, to help the working class, the wealthy must be deregulated.

Let’s take this quote from the US Department of Labor,

The days of waste, fraud, and abuse are over. The Trump administration is bulldozing through red tape and big bureaucracy, returning freedom and purchasing power back to hardworking men and women.²

And,

Workers feel heard, respected, and empowered by this president.³

In what sense does bulldozing government programs give power back to workers? Do they vote for their CEOs, managers, wages, and so on? Do they vote for the oligarchs that control what they see and hear? The oligarchs who placed them in debt and increased the costs they’re so concerned with in the first place?

While we can choose what to buy, what we buy is to a degree determined by our income status, the advertisements we see, the retailers we have access to, and so on. We don’t have absolute freedom of choice in this case, thus we do not have a ‘free’ economic ‘vote’. In other words, purchasing power, which, in the above passage, is equated with ‘freedom’.

We have a range of choice, but that range is decided by factors either out of our control, or within our control but in which our control is limited. If I am poor, it is decided by demographic, region, lineage, and so on, as much as it is decided by personal choice (with exceptions, of course; e.g., addiction); if I am rich, it is the same way, and my purchasing power is determined solely by the value of the given currency.

So unless one runs society, they are the exploited — not the exploiter. The only true power they have is over the ‘democratic’ state, thus the only power they have is through regulation of that which they have little power over.

But even in my case, I operate under certain assumptions, such as the idea that ‘democracy’ implies universal power, as opposed to the opportunity for power; that a state in the midst of a democratic backsliding is better than an already undemocratic market; that a politician is better than a CEO, and so on.

But Trump understands — or at least functions as if he does — this signification process, alongside the contradictions baked into his thought. Let’s take this quote from his 2019 State of the Union address,

America was founded on liberty and independence — not government coercion, domination, and control… Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.⁴

Trump signifies past Marxist-Leninist communist regimes as the blanket term ‘socialism’, thus ‘oppression’ with ‘state-economic-power’, even if that state power is fundamentally different from the authoritarian hellscape his supporters fear. He signified normally socialist signifiers (working class liberation) as per a fascist ideological field. He took working class concerns and didn’t justify the right wing, but attacked the solutions to his voters’ problems and propped up himself and his economic class in the process. This also allows him to act as an authoritarian, doing precisely the “government coercion, domination, and control” he is quoted as opposing, as authoritarianism is reframed as a socialist symptom — one which is impossible under a non-socialist system such as his own.

This indicates something even more important: the working class has the same concerns practically universally. Bernie Sanders ran a tremendously successful presidential campaign in 2020, and proves himself still to be the most popular member of congress, meaning he is crossing the party line. He and Trump said they’d solve similar problems with different solutions, but, in the end, the American people simply wanted something consistent: some kind of change and a solution to their problems.

Division is even more deep-seated than before. Each side hates the other because they truly, in the most honest of ways, feel the other is destroying the country, as they fundamentally disagree, not on principle, but on definition. To one side, freedom means freedom from taxes and corporate regulation, to the other it means economic justice. Yet even economic justice means two different things. Economic justice could mean justice to imperialists and freedom from exploitation, to others it means the freedom to hold property. And what is property? Some may say it’s a path to theft, the other may declare their opposition to be the thieves.

This division won’t disappear with respectful discussion or unity of any kind. It’ll always exist, because in the end, it isn’t just ideological.

From the Human Rights Campaign,

Polling indicates that 64% of all likely voters, including 72% of Democrats, 65% of Independents, and 55% of Republicans think that there is “too much legislation” aimed at “limiting the rights of transgender and gay people in America.”⁵

The majority of conservatives take little to no issue with gay and transgender people, yet Donald Trump is known to be devoutly opposed to them, believing that they are a terrible problem leading to the corruption of moral society, pushing the need for book bans and restrictions on childhood expression of queer identity. Trump and the GOP as a whole, given hundreds of anti-transgender bills have come out in the past few years, would make such people out to be extreme threats and those who respect their right to live to be radicals and extremists. If congress mirrored the will of its voters and the news media honestly portrayed public opinion, transgender people would face little oppression. Yet, they face such oppression, indecating that this problem is not one of ideology, but one only pervasive within the ruling class.

‘Freedom’ is thus signified as freedom from the expression of minority identity, ‘immorality’ is signified as ‘queerness’, ‘extremism’ is signified as ‘social liberalism’, and basic queer expression is retroactively made into an ideological imposition. Those who support such ‘impositions’ are turned into scapegoats — alongside the queer community — for ideological oppression and social degradation, among other things.

This is arguably the most important thing to consider in understanding ideological dogmatism. To return to the previous example of communism, Zizek writes,

‘Communism’ means (in the perspective of the Communist, of course) progress in democracy and freedom, even if — on the factual, descriptive level — the political regime legitimized as ‘Communist’ produces extremely repressive and tyrannical phenomena. ‘Communism’ designates in all possible worlds, in all counterfactual situations, ‘democracy-and-freedom’, and that is why this connection cannot be refuted empirically, through reference to a factual state of things.⁶

To use this passage in our context, rational argumentation becomes impossible, as (1) opposing sides operate with different definitions; and (2) contradictions are inherent to the quilting process, yet this process still goes on, so contradictions to a given ideology are by default meaningless.

This signification is not the product of a working-class spontaneously animated toward general purpose bigotry, nor is it necessarily religious. Protestantism has little consistent stance on queer issues (many churches and theologians — and I am inclined strongly to agree with them⁷ — are highly supportive of the queer community), and the Catholic Church has roughly the same inconsistency, but the simultaneous stance that such people should be respected and loved regardless. Neither the church nor the Bible advocates for religious state intervention, and historical situations to the contrary have often been pandering by the church to the state to accumulate wealth and power — a class based distortion of scripture.

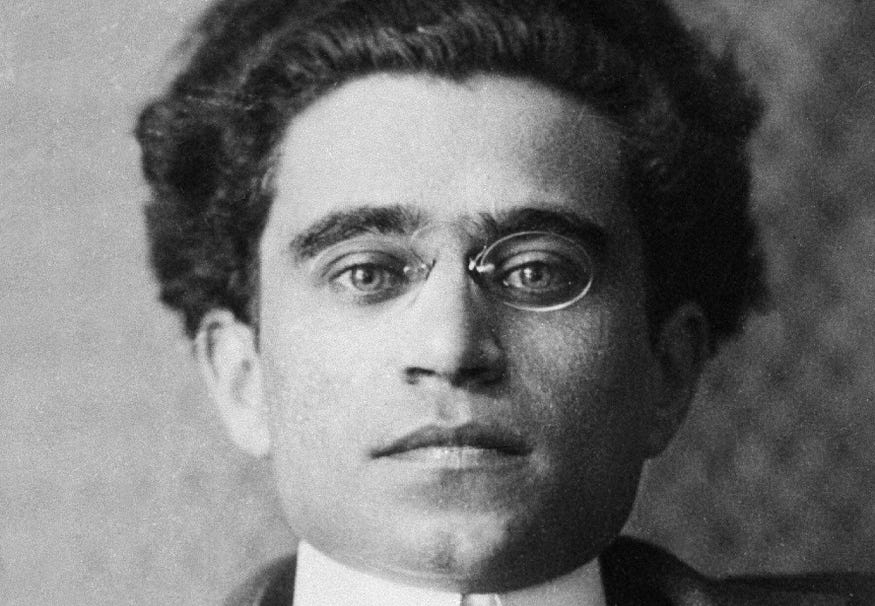

Thus, such an animation is a product of those who seem to care — those who establish transphobic and bigoted policies. This is the central problem: it is not the powerless, but the powerful, who are causing this division. It is not ideology on its own, but, as Gramsci put it, cultural hegemony. The working class is exploited, not just materially, but ideologically, by the property holding and political classes.

¹Slavoj Zizek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 1989

²Lori Chavez-DeRemer, 100 days in, Trump’s Golden Age puts American workers first, 2025

³Ibid

⁴Library of Congress, President Donald J. Trump’s State of the Union Address, 2019

⁵Cullen Peele, Reality Check: Public Opinion on LGBTQ+ Issues Ahead of Second GOP Debate Highlights the Failure of Extremist Attacks, 2023

⁶Slavoj Zizek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 1989

⁷I’m tempted to write an essay on this problem in the future, if only for myself in order to organize my thoughts.